Installable webapps: extend the sandbox

Have you seen the extensible web manifesto? It's the formalization of a recent trend in web standards: a tendency towards lower level APIs. Lower levels of abstraction enable developers to build more on top of a solid foundation. By going down a level of abstraction in the web platform, web developers can contribute to the platform itself in a more fundamental way, working along with browser vendors and spec writers. This is how the web should work.

But there is a big missing piece in the extensible web vision. Our beloved platform is stuck in a constrictive security sandbox. The "drive by" web's security philosophy is that users of the web should be able to feel safe on any webpage they visit. While very important for the well being of web denizens, it prevents developers from using increasingly important features enjoyed by native platforms such as access to contacts, TCP/UDP sockets, interfaces to external USB/Bluetooth devices. Breaching this sandbox is a huge barrier for the web as a compelling application platform.

Some recent features, such as getUserMedia, which gives web developers

access to the audio and video streams of your device's camera and

microphone, have started to break out of the sandbox. There are two

approaches to this problem today: (a) infobars and (b) packaged apps. In

the rest of this post I'll describe why these are bad solutions,

deconstruct them down into small pieces and then glue the pieces back

together. The ultimate goal is a modest proposal for installable web

apps. Read on for my take on the background of the problem, or skip

ahead to read my illustrated proposal for fixing it.

The extensible web is a good idea

There are many recent examples of the extensible web philosophy across many areas of the web. Because of the low level nature of WebGL and Web Audio, these technologies open up a wide variety of applications to be built. Under the hood, these APIs are relatively thin wrappers around underlying native technology, not compromising performance (much) while adding developer usability. General purpose low level computing technologies like asm.js and NaCl enable computationally intensive algorithms to run far more efficiently.

Finally, frameworks like Polymer use other kinds of low level APIs like web components and model-driven views to let developers invent new types of HTML elements with custom functionality.

Sandbox vs. low level APIs

Restrictive web security makes a lot of sense. You should never have to

worry about malicious or careless developers erasing files from your

local filesystem, even if you frequent the most notorious .ru domains!

That said, if the web is to be a viable application platform that stands

a chance against native platform, it needs to have access to certain

data that is sensitive.

Many of the APIs that align with the extensible web philosophy have

already tested the bounds of the web's sandbox. Some have resulted in

security vulnerabilities, such as 2011's cross-domain WebGL texture

attack. Others have required extending the web platform

with additional levels of security. The earliest of these is probably

the geolocation API. More recent additions include getUserMedia, which

gives developers a stream of the microphone and camera. These APIs could

obviously lead to very serious privacy breaches if turned on by default

on all web pages. I don't want the Russians knowing where I live, or

eavesdropping on my conversations (NSA already knows).

The "drive-by" web solves this problem through infobars. I will explain later why this is a terrible idea. The other solution is packaged web apps. Packaging circumvent the web completely by copying the distribution model of native apps, bundling your whole application into a locally downloaded zip. This model also features an installation step which sometimes also grants additional permissions up front. Both of these so-called solutions reduce the likelihood of new low level APIs from coming to the web platform.

Infobars are a bad user experience

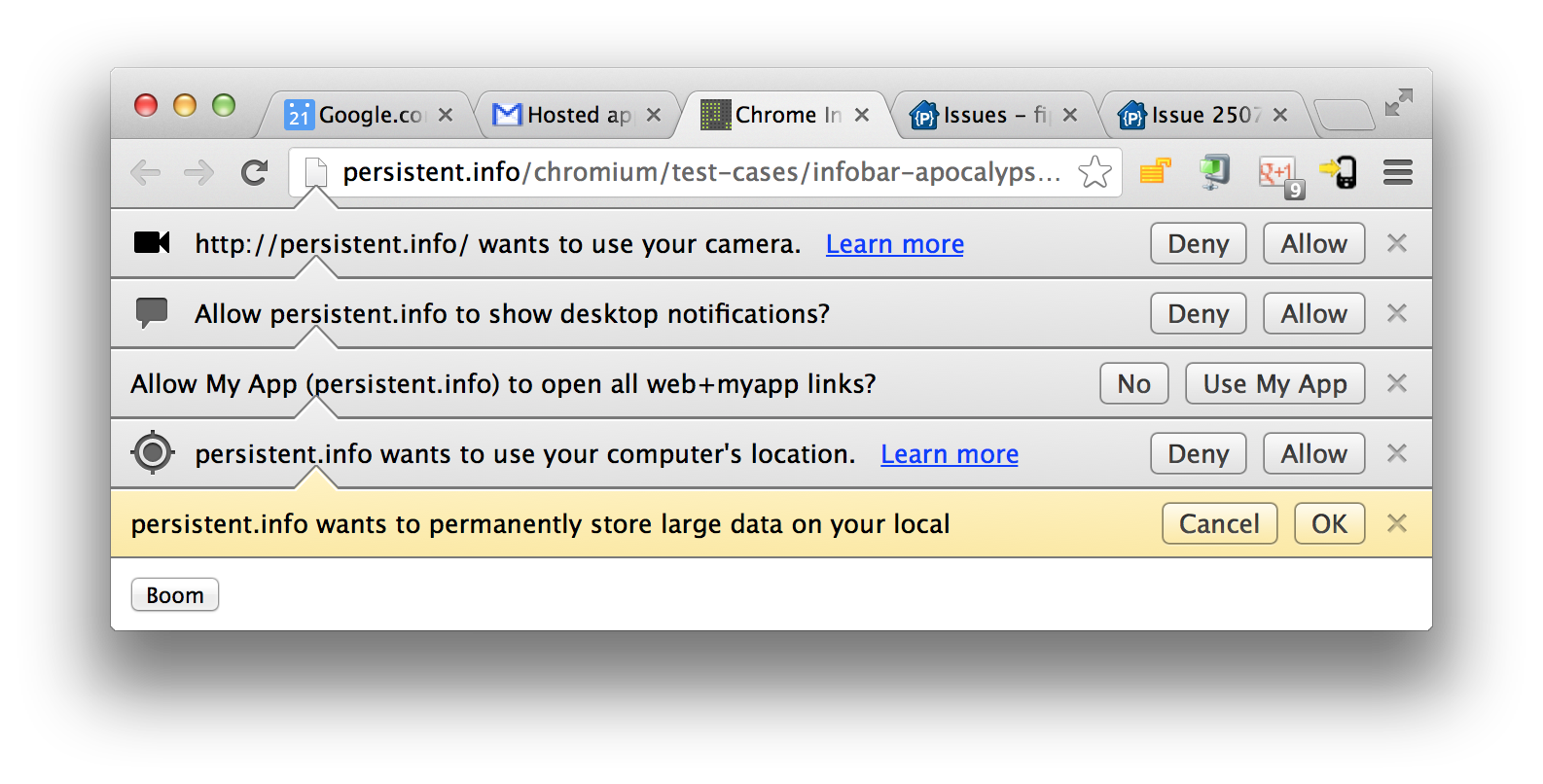

First, look at this:

This gem, courtesy of Mihai Parparita, is my favorite explanation for why infobars suck. You can immediately see several problems stemming from the obvious fact that the infobar model does not scale well. In the infobar world, each feature requires its own permission, leading to far too many stacked dialogs that are just ugly. From a usability perspective, your users have to click through each one of the Allow/OK dialogs before they can do anything with your application. If you then reload the page, many of these infobars will again return to haunt you, forcing you to click OK five more times before being able to use the webapp.

In some cases, your browser might remember that you accepted an infobar,

and choose not to show it to you again. For example, this happens if you

grant getUserMedia access on an HTTPS site, selecting the "save this

preference" option. This is remembered on a per-domain basis, and in

Chrome, is available via Preferences -> Content Settings. In general,

conditions for when exactly the browser remembers how you responded to

an infobar are unclear and underdefined.

There are also some less obvious issues with the infobar model. Because infobars are non-modal, users often don't realize that they have to accept them before they can use the webapp's functionality. For example, if you have a photo booth application, it will be completely useless until you accept the "access to video stream" infobar, yet many of your users may not notice the infobar at the top of your browser window. If you attempt to draw your users' attention to the infobar via some illustration, you may end up pointing to the Deny button by accident because of variations in placement across various browsers and browser versions.

To summarize, infobars are broken in the following ways:

- Does not scale with number of permissions.

- Visually jarring at scale. Sometimes not visually obvious enough.

- Permission granting should often be modal.

- Inconsistent persistence, poor management.

Part of the problem might be addressable via a visual refresh of infobars (as Paul Neave suggests), but I suspect that a broader rethink of the problem is in order. Until this is resolved, many new low level APIs will increases Mihai's stack of apocalyptic infobars, reducing their chance of coming to the platform in the first place.

Packaged apps...

Packaged apps are an odd marriage between native app distribution and web technologies. The packaged web app model consists of a few moving parts:

- A directory for discovering and installing apps (eg. Firefox Marketplace, Chrome Web Store).

- A set of platform-specific APIs built on top of the web platform for use in these apps.

- A manifest describing each app, which can specify permissions to enable either the above platform specific APIs or restricted open web APIs.

There are certainly benefits to this approach, such as a sane offline story, since all of the assets of the application can be packaged together into a bundle that is downloaded at install time, circumventing painful technology like AppCache. There is a clear install step, during which you can grant an application permissions beyond the scope of the open web platform. Also, it's very easy to add features to packaged apps, since there are no annoying standards to worry about, amirite?

...are bad for the web

Unfortunately, packaged web apps provide the worst of both worlds, combining relatively poor web developer ergonomics with the longer development and distribution cycle of native apps. Also, many of the drawbacks of packaging are at odds with the philosophy of the open web platform.

The first and most obvious problem is the lack of URLs for packaged apps. URLs are critically important as unique identifiers for content found on the web. They are great for sharing content, indexing, and bookmarking. Secondly, there is no standard packaged app format across platforms, which means that the packaging formats and APIs available are completely different between Chrome, Firefox, and other packaged app providers. This cross-platform aspect is the main economic reason to develop for the web. Another drawback is that each of these packaged app vendors has its own app store, sometimes complete with approval processes similar to the much reviled App Store approval flow.

Lastly, once a browser vendor has a packaged app model, it's very tempting for them to just implement new low level features there and not on the open web. This effectively lifts the pressure for browser vendors to go through the pain of standardization. The standard response can now be "just go build a packaged app". A summary of these issues with packaged apps:

- No URLs

- Not cross platform

- Dependent on centralized directories

- Vendors have an excuse to punt on adding new features to the web platform.

Packaged apps are at odds with the web. To the unintiated, it feels as if their inventors slapped web technology on top of the Apple app store model. I know that there are some legitimate, security-motivated reasons for their decisions, but believe that these are surmountable.

Installable web apps

If you have an iOS device at your disposal, take a look at forecast.io. Forecast.io is an example of an app you install from the web. This approach is interesting because it combines the best of both worlds. On one hand, you retain the benefits of the web: URLs, cross-linking, lack of centralized control. On the other, you get the benefit of elevated permissions.

A benefit of this approach is that there is a clear install step during which you can request additional permissions, which is a natural place for breaking out of the web's sandbox in a user-friendly manner. The result of installation is a homescreen shortcut, which is both a launch convenience, and a way of managing permissions. Removing that shortcut can also mean revoking special permissions for that application.

Another benefit is that there is no centralized appstore - you can discover apps in the same way that you discover the web today - through search engines, links in your email inbox, feed readers and through any other URL-based sharing scheme. There is no reason to conflate installation with the presence of a centralized directory. Google search is already revealing apps in search results. If you search for "Angry Birds", you will find both the iOS and Android versions on the first page.

Proposal: apps you can install from the web

So far I've described the problem: a major barrier to the vision of the extensible web: there is no good way of getting outside of the sandbox. I have been complaining a lot without providing any constructive answers.

In order to keep things constructive, the second half of the post proposes a solution to get us out of the sandbox. There's a whole world out there! Here is my birds-eye-view of the install-from-the-web world:

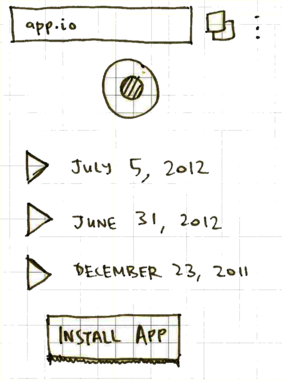

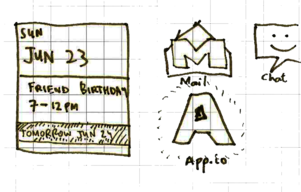

This diagram is intended to be general enough to work across

operating systems and device types, but the mocks themselves will be

sketched out with a phone form factor in mind. We'll be installing

app.io, a mobile app that lets you leave audio notes.

Screen 1: App.io example.

An API for installing webapps

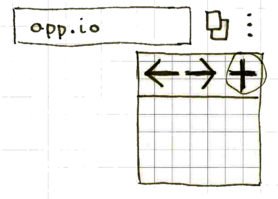

This can be done with an iOS-style approach (and corresponding Chrome for Android feature request), which presents a generic UI for adding apps to the homescreen (see Screen 2).

Screen 2: Add via browser button.

There are trade-offs between having a button or an opt-in developer API for installing web apps. With a button, any URL can be added to the home screen, which may not make sense. But with an API, the developer has to provide an explicit call to action for you to install their app. The button UX will always be consistent, since it's part of the browser. An API-based install path may be ugly or spammy. However, an API can also provide a consistent experience across browsers without the need for guessing where each browser places the button. Many forecast.io-style apps on iOS have callouts on the page pointing to the button in the browser chrome which would be broken if another browser had a different method of adding to homescreen.

My opinion is that button- and API-based approaches both have a place. For webapps that make more sense installed, the API can be a nice touch. Other pages might be useful as webapps without their developer realizing it, so the button-based approach is useful there.

How would the installation API look like? A JavaScript-based API only callable on user action, similar to how audio playback in mobile browsers prevents the annoying situation where visiting a page automatically prompts you to install it. Installing a webapp should come with a default set of permissions above and beyond what the web platform provides.

var button = document.querySelector('button#install');

button.addEventListener('click', window.app.requestInstall);

You should also be able to request additional permissions at install-time. For example, to request installation and audio capture, the following code should work:

window.app.requestInstall({permissions: ['audioCapture']});

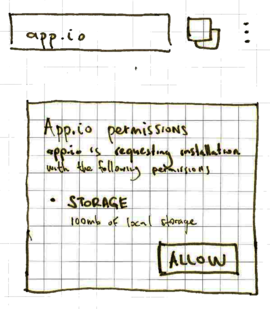

This action should also result in a standard browser-specific dialog to accept installation, showing which permissions have been requested (Screen 3).

Screen 3: Confirm installation.

Once accepted, a launcher shortcut should be created (Screen 4). Two pieces of metadata are necessary for this launcher:

-

Icon, which should first look for a large enough version of the multiresolution favicon as determined by the UA. If none exists, it should look for the apple-touch-icon in the

<head>. If none is specified, a screenshot of the page can be used as in iOS. -

Title, which can be extracted from the

<title>element in the head. If none is specified, the user can be prompted to input their own title.

Screen 4: New launcher added to the home screen.

Launching in standalone mode

iOS already has an API to know if a webapp was launched in standalone

mode (ie. from the launcher) or if it was opened from a browser. This

functionality is available via window.navigator.standalone. It also

opens the app in full-screen mode.

Other vendors should standardize and implement similar functionality.

For example, something like window.app.standalone, if only for naming

consistency could be implemented, and a polyfill provided for the Apple

spec. It would also make sense to launch homescreen apps in full screen,

providing the same UX as the full-screen API (Screen 5):

Screen 5: App launched in standalone mode.

Requesting additional permissions

Apps might need additional permissions that go beyond the default baseline of permissions granted to the app at install time. Access to your camera would fall into this bucket. An API call to request extra permissions might look like the following:

window.app.requestExtraPermissions(['videoCapture']);

Running this command would also require user-initiation and prompt a

modal optional permissions dialog (Screen 6) similar to the one seen at

installation. After granting it, the associated API call (in this case,

getUserMedia) can be invoked without incurring any infobars.

Screen 6: Additional permissions request.

Removing installed web apps and extra permissions

If the installed webapp has a native launcher, removing the launcher can do this implicitly. There should also be a browser- or system- UI similar to existing app management interfaces that lets you remove installed apps, or revoke granted permissions.

That's it folks

So there you have it: my strawman fixing the security model of the web,

which, as I outlined at the beginning of this post, is

critically important to address for the continued success of the web.

To recap, the solution consists of an API surface in the window.app

namespace, and a number of new screens that are part of the installation

process.

If tackled, this could solve one of the most important issues on the web today. Otherwise, we may find ourselves in a place where the web platform is irrelevant to application developers, who will just build for packaged platforms.

I'm not silly enough to think that this proposal is the ultimately correct and best solution for elevated priveledges on the open web. There is a huge amount of work required to refine the flow, think of all of the edge cases, implement it across browsers, etc. The above is just a draft to re-ignite the web permissions discussion that died several years ago. Please blog something in response or in the worst case, tweet or email your opinion. Looking forward to hearing from you.

Update: important links

July 18, 2013: Several people have pointed out that I've missed some important links. My public apologies!

Chrome hosted apps are a somewhat similar concept, but suffered from security issues that still need to be resolved to make this proposal a reality. There was even an effort to make hosted web apps installable from the web, called CRX-less web apps (preserved on Mihai's blog), which today is little more than a broken link.

To my knowledge, the most active project along the lines of this proposal is the Open Web Apps work from Firefox OS.