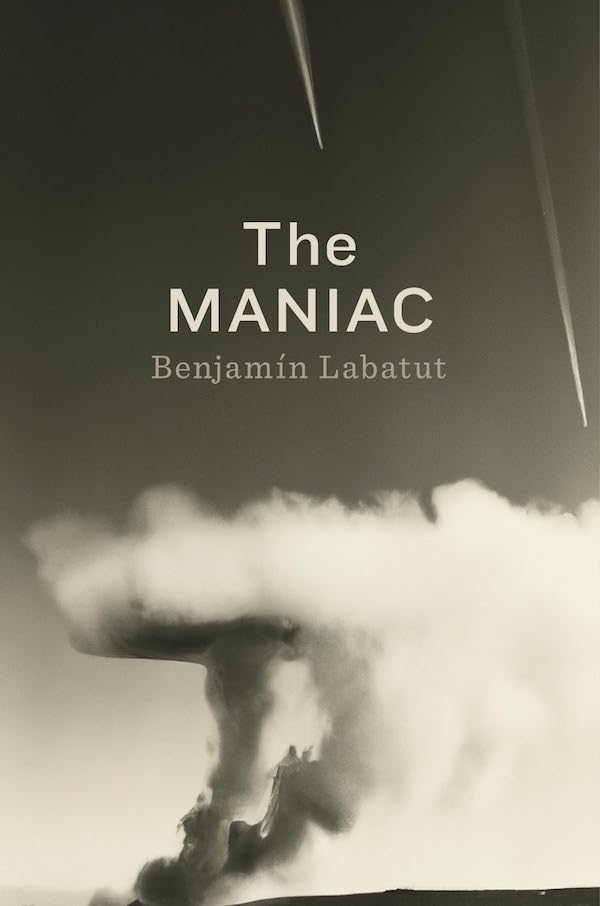

The Maniac by Benjamín Labatut

I recently watched a movie called "The Bit Player" bankrolled by IEEE, about Claude Shannon and his contributions. The film was informative something was a bit off. In what could be described as a fauxcumentary or docudrama, Shannon was portrayed relatively convincingly by an actor, but rather than creating a narrative arc of his life and work, this fake Shannon was portrayed in a sequence of reenacted interviews. Some of them were informative and entertaining, others cringeworthy and irrelevant, almost bordering on mockumentary.

Upon reflection, I found "The Maniac" a little bit like "The Bit Player", which surprised me since like its predecessor it straddles this same fact-and-fiction line. Either under the influence of the Shannon documentary or because it is simply worse I enjoyed this book far less. Another contributing factor was perhaps that I listened to it as an audiobook and the narration, especially the female narrator who played Von Neumann's wife and daughter had a distracting accent, serving only to fortify the idea I just couldn't shake that these historical figures were just pantomiming actors.

Parallels to the 1920s: The anxious, tumultuous interwar vibe of the 1920s (“we knew that the wonderful world that was built for us was coming to an end”) reminded me of present-day feelings of precariousness. Both eras are shaped by major innovations (whether quantum theory or AI) combined with rapid political shifts to produce a collective sense of uneasy acceleration.

Von Neumann’s Intellectual Legacy touched many pivotal 20th-century developments: designing the first fully programmable computer (the “MANIAC”), formulating the principle of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD), and conceiving of self-replicating machines well before the structure of DNA was even understood, as well as “von Neumann probes”, self-replicating spacecraft that could travel to the far reaches of the galaxy. This was simply interesting.

His frenetic personal life is a stark contrast with his boundless intellectual curiosity and comedic playfulness. The most disturbing were his late-in-life dabbling with religion: frenetic forays into his native Judaism, and a last-ditch conversion to Catholicism.

Computing and the Hydrogen Bomb the development of the hydrogen bomb required massive computational power. Human “calculators” could no longer handle the complexity; thus, machines like the MANIAC were indispensable. This foreshadows how computing became the central engine driving modern science and technology. Getting to many destinations requires tacking (zig-zagging)

Creativity, Play, and AI John von Neumann and Richard Feynman valued playfulness and curiosity in serious scientific inquiry. That said Labatut also did a good job of showing the perils of excessive playfulness: a certain nihilism and psychopathology. AI has taken a narrow path to mastery (AlphaZero’s pure self-play in Go), but still lacks the open-ended, playful immersion children show when learning. Can advanced AI develop a truly exploratory, flexible sense of “play” in the real world, rather than in highly constrained settings like Chess, Go? LLM advances for "play" in LLMs is very impressive, but the real world is more complex still. See Physical and embodied intelligence.

AI’s Impact on “Art” is so far quite destructive. Lee Sedol lamented that Go used to be an art form but has changed now that AI dominates the game. A similar thing is happening with "Ghiblification", in which a beloved aesthetic that once took years of human effort can be conjured in seconds. This touches on a broader debate: Does AI’s involvement in creative or aesthetic fields reduce them to mechanical processes, or does it expand the boundaries of creativity?

Extended Phenotype and Technology: A spider’s web or a beaver’s dam are examples of the extended phenotype of their respective creators. Can we view technology as extended phenotype of the human? See Extended phenotype — technology as human secretion.

The Legends of Go are really awesome. This was probably my favorite part of the book. Labatut evocatively describes the legendary Emperor Yao who invented the game of Go to challenge his wayward, evil son Danzhu. The victor would rule the universe. It seems like Labatut greatly embellishes the traditional tale, but it's worth it. Another memorable Go story retold in the second part of the book was that of the blood-vomiting game of 1835 which lasted four consecutive days after which the loser Akaboshi coughed or vomited blood all over the board, dying within a few months.